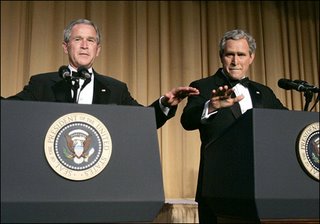

Bush's sense of self-derision.... and its limits.

It is hilarious (watch the video here or here)and I must admit that it takes guts for a president to go that far. It does not make him a better president but it shows he has a good sense of self-derision at least, which may be a sign of intelligence.

It is hilarious (watch the video here or here)and I must admit that it takes guts for a president to go that far. It does not make him a better president but it shows he has a good sense of self-derision at least, which may be a sign of intelligence.The president makes decisions, he’s the decider. The press secretary announces those decisions, and you people of the press type those decisions down. Make, announce, type. Put them through a spell check and go home. Get to know your family again. Make love to your wife. Write that novel you got kicking around in your head. You know, the one about the intrepid Washington reporter with the courage to stand up to the administration. You know--fiction.Apparently that was not appreciated by some of the press nor by the president. So there are limits to his sens of self-derinion. Bush quickly turned from an amused guest to an obviously offended target as Colbert’s comments brought up his low approval ratings and problems in Iraq.

If you watch the whole thing (available here via Crooks and Liars), you may find it a bit long and not always funny but the attack on the press feels good. As DailyKos noted, if this president is bad it is also because "we have the worst, laziest, and most irresponsible media since the bad old days of yellow journalism".

I also share this final thought on the issue by Peter Daou who wrote that:

Bush's clownish banter with reporters - which is on constant display during press conferences - stands in such stark contrast to his administration's destructive policies and to the gravity of the bloodbath in Iraq that it is deeply unsettling to watch.